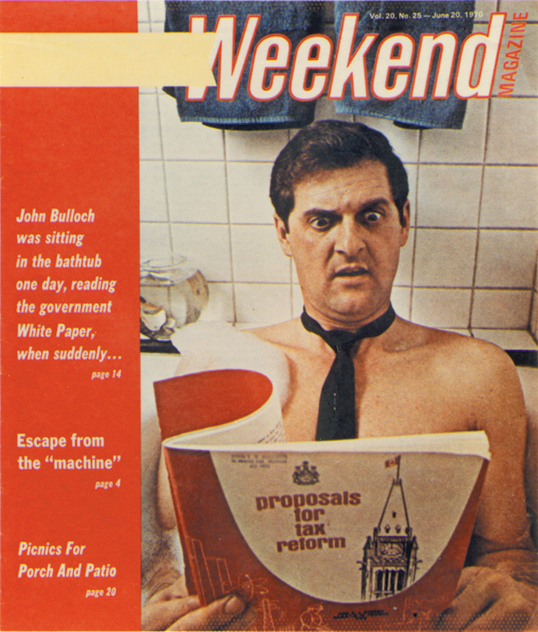

When I read the White Paper on Tax Reform introduced by Finance Minister Benson in 1969, I was relaxing in the bathtub, part of a regular soak after a day of teaching. This bathtub story later became the basis for a front-page photograph and article in Weekend Magazine, that was a weekly supplement in newspapers across Canada.

When I read the White Paper on Tax Reform introduced by Finance Minister Benson in 1969, I was relaxing in the bathtub, part of a regular soak after a day of teaching. This bathtub story later became the basis for a front-page photograph and article in Weekend Magazine, that was a weekly supplement in newspapers across Canada.

Although I was not an authority on our tax system, I knew enough about it as a finance teacher to understand roughly what the government was proposing. Firstly, they wanted to tax small business corporations at a rate of 50%, which on paper was the rate large corporations paid. But based on a study I had seen at Ryerson, the effective rate of tax paid by large multi-national corporations was closer to 25%.

Another shock was the proposal of a capital gains tax on death on top of provincial succession duties and federal estate taxes. It was an obvious plan to confiscate private savings.

Now it was my nature, when seeing something that is not right or does not seem to be right, to try and do something about it. So I decided to write a letter of protest to Finance Minister Benson. I figured no one would really read this letter, so I asked my father to post the letter within one of his ads in the Globe and Mail. That decision changed my life and was the basis for a whole new career.

At least once a week, father placed a two-column ad that ran on page two. It combined religion and politics and the sale of his made-to-measure suits. It was called editorial advertising, and he was the pioneer. He had a huge following. What a surprise when the advertising manager of the Globe told him that the readership of his ads was higher than the readership of their editorial page!

Well, the explosion of interest in my letter was not something I had anticipated, and the morning the ad appeared, the three phone lines at the Bulloch tailoring store lit up and stayed that way throughout the entire day. One of Dad's sales staff was sent over to Ryerson to bring me to the store and help field these calls. I cancelled my remaining class for that day and headed over to the shop on Bay Street. What I discovered was eight pages of names and phone numbers of call-ins. I filled another eight pages while I was there for the remainder of the day.

I made a list of what seemed to be the ten angriest callers and called them back and suggested a meeting. One of the callers was John Hull, the President of Public Relations Services Ltd., and he offered his Board Room for a meeting. The first meeting ended with a decision to meet again after consulting any legal or accounting experts we knew, and to bring $1,000 each so we could get some form of opposition organized.

When the next meeting was held, only John Hull and I showed up with our $1,000 cheques. My cheque was written by my father from his own bank account. I said I would try to get a leave of absence from Ryerson for a year, with my father covering my salary. John Hull offered some space next to his office that we could use. We decided to create a new not-for-profit organization called the Canadian Council for Fair Taxation. My new life was born.

It is often called the Law of Unintended Circumstances, when you act in response to an event and are unable to really know the consequences of what you are doing. From my experience, it is impossible for anyone to exercise leadership if they are not entrepreneurial by nature. Entrepreneurial people make things happen. And when they try to change things, they often re-route their lives and the lives of others in unanticipated directions.